“Not every woman can be a beauty, but every woman can behave like a beauty,” wrote Mrs. Walter Sohier in Vogue’s February issue, 1950. These words may seem ancient to the iPhone-tapping, degree-earning, freedom celebrating women of our day, but has the message behind these words really left us?

Magazines first started earning million dollar revenues in the 1970s and yet, 40 years later, media remains a chilly, disciplined and sometimes even painful world for women — most especially, for girls. Even over the past three centuries that women have been reading magazines, its easy to notice that while the real, the unkept, the unpredictable and the free all seem to roam in news publications, the same isn’t necessarily true for women’s and fashion magazines. Concerning visual narratives and threatening unwritten rules can endanger young minds.

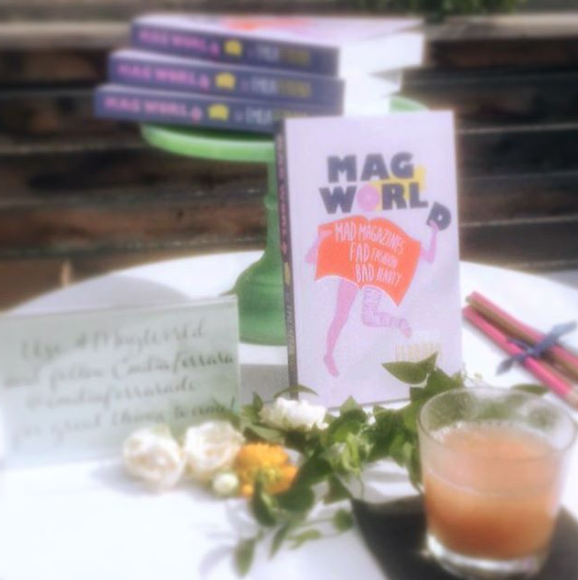

Emilia Ferrara was a captive magazine reader, pouring through every page of every issue, month after month, in her teens through to college. However, as her passion for journalism grew, her inclination to serve the female reader through female titles waned. After repeatedly encountering frivolous narratives and unhealthy standards, she began studying at Columbia Graduate School of Journalism and researching how the beauty, fashion and magazine industries impact young girls.

“Mag World: Mad Magazines, Bad Beauty, Fad Fashion And Finding The Way Out” is a non-fiction text that threads together voices such as Virginia Woolf, Walter Lippman and Tina Fey. Ferrara speculates over the future of girls as readers, much like Woolf imagined the future of women writers. She challenges intricate details of modern journalistic practices, adjacent to Lippmann’s review on his day. And her hopeful (and sometimes humorous) tone echoes Fey’s ability to deliver a positive critique.

Written with both vision and forgiveness, Mag World is a melodic call for reform, a handshake to editors and an inspiration to today’s girls who stand to inherit the future. This brave and gracefully defiant journalist shows the way forward for all who aim to serve this next generation of young readers. With profound empathy and radiant imagination, Ferrara encourages each of us to see beyond the cover, the label or the selfie and to believe that the world of media can be healthy when we dare to change.

available on

excerpt

“I want to approach the grayscale I introduced a few moments ago: is fashion about self-expression or is fashion about identity? The basic framework behind the argument that “fashion is about self-expression” is that fashion is a choice. You don’t grow clothes. They don’t magically manifest on top of your skin. You choose them, or you choose the person who chooses them for you.

But is every piece of clothing a piece of the self? Certainly not. This is why the latter statement exists on a grayscale.

Character and identity are not the same thing. If you have a piece of wood and you hack at it a thousand times until it becomes a perfectly smooth baseball bat, you have gradually, habitually formed a shape. One day it’s a block of wood, and a few weeks later it’s a baseball bat. Now, if you drop your bat down a flight of stairs, leaving a one-inch gash across the surface, it is still a baseball bat—it is not “a gashed piece of wood.”

Identity can be influenced by mood—but character cannot. Character is who you are, slowly formed over time. Getting dressed each day is a routine honed by many small decisions, much like slow tiny chisels into a piece of wood. If I have always been blonde, you would try to identify me walking down the street by my hair color. If I dyed it brunette, you might not recognize me right away, but you would eventually adjust. If I have always been friendly and I passed you on the street and said hello, it would be familiar because you know me to be an engaging person. If I passed you on the street, kept my sunglasses on, continued typing into my phone, and didn’t stop to greet you, you would pass me and immediately wonder: was that her or someone who just looked like her? Identity may undergo superficial tweaks (our hair color, our contact lens color, even our name); but character, however, cannot be quickly flipped. Character is more related to self-expression because our “self ” is the most intimate contact we have, and characterization is the self ’s slow development through life. Identity can be changed as quickly as a spy putting on a different wig.

Accepting fashion and style as necessary tools to form character brings up the highly contentious element of authenticity (contentious, especially among those who follow the fashion of Hollywood). Carrie Bradshaw, for example, was keen on mixing and matching; it would be a vintage leopard tube top one day and a couture pinstripe pencil skirt the next. Sarah Jessica Parker’s ballet body gave a graceful yet strong carriage to these outfits, allowing her character the alacrity necessary to engage with such a diverse and lively wardrobe.

Nevertheless, it is not true that Carrie loved “costumes.” She was not randomly and unnecessarily grabbing loud and outrageous clothes. Carrie’s closet expressed her character in two ways. First, as a journalist, it was her practice to enter and exit the richly varying lives of New Yorkers, and for this transit her closet reflected a chorus of voices—not unlike the panoply of quotations you would see if you flipped through her portfolio of columns. Secondly, Carrie’s closet did have high-octane pieces she would mix in from time to time because Carrie herself lived a very intense life. Her entire column was about seeking both the thrill and the intimacy that sex can offer in a city so cavernous it seemed unending in its possibilities. An alarming orange jacket or a pink ballerina skirt vibrated at a particular frequency because Carrie wore her heart on her sleeve, and there was nothing mute, coordinated, or classic about it.

If we can consider Carrie’s wardrobe to be natural for her, as opposed to a random exercise of costume parading, then we can understand why authenticity—not performance— is more important to fashion. I grew up a ballerina. My father loved opera; my mother loved the theater. I’ve seen my fair share of costumes. They are irresistible pieces of art and sometimes brilliantly simplistic (enter: Annie Hall). But we cannot deny the great gap between couture and The Gap, between the runway and your sidewalk, between Chanel and a purse. To be sure, the Costume Institute in New York would vehemently agree.

I do not argue that there is no difference; rather, I challenge both the importance we misplace as well as the flow of influence we misidentify. How can it be that costumes are more important than clothes? How can it be that the more whimsical piece from a runway predominates evolutionary style hierarchy over the clothes we see down the street? Is it always true: the rarer it is, the more important it is?

Allow me to answer that question by picking a bone with the fictional Miranda Priestly…”